Bear Alert! The paper sign hung from the window of the Gooseberry Falls campground office. Below the warning was a photo of an intimidating black bear and instructions for shooing him away from our campsite. We had traveled five hours north to Lake Superior, through the port city of Duluth, and deep into the north woods. Deep into bear, moose, and wolf habitat. I had hoped to see all three—preferably through binoculars or from a car window.

As we studied the campground map, the park ranger filled us in. Bears had been reported at several campsites over the past week despite being rare in this particular state park. For unknown reasons, they seldom crossed the scenic byway that formed the park’s western border. Then again, it was early September and fall was coming fast in the north country. Evenings arrived in cool shadow, nights were hushed with no more frog song or buzz of insects. As hibernation time drew near, the bears’ appetites were growing. Roaming the woods like insatiable teenage boys, eating becomes a full-time job for the black bears. The ranger warned us to stash anything that had a strong scent, even lip balm. My thoughts turned to the Hawaiian Tropic sunscreen I slathered on each morning that left me smelling like a coconut macaroon. A giant coconut macaroon, conveniently packaged every night in a pink nylon sleeping bag.

Like a lot of people, my fear of bears is overblown and heavy on myth. The truth is, black bears are wary of people. While they’ll eat small mammals or the leftovers of other animals, human beings don’t make their list of desirable meals. A rundown of the bears’ diet sounds more like a recipe for trail mix than the quarries of fearsome predators: grasses, insects, and berries in the summer, transitioning to acorns, hazelnuts, and other tree nuts in the fall. The upper Midwest, with its rich plant life and sparsely populated northern forests, is perfect black bear habitat. Wisconsin has the highest population of black bears in the continental United States with about 35,000 bears (Alaska, not surprisingly, has more). Its neighbor Minnesota—my home state and where we camped—has around 20,000.

Despite these numbers, the Minnesota DNR has recorded just 12 bear attacks (or “near attacks,” depending on how you define them) since 1987. In most of these encounters, the bear reacted in self-defense or surprise. Last year, a bow hunter was attacked by a black bear in northern Minnesota, making headlines across the state. He and his companions had shot and injured a bear and then lost track of it for several hours. The hunters surprised the wounded animal, still alive and angry, in the woods around midnight. The bear attacked. Fortunately, after a terrible struggle, the hunters escaped without any permanent injury. The bear was killed.

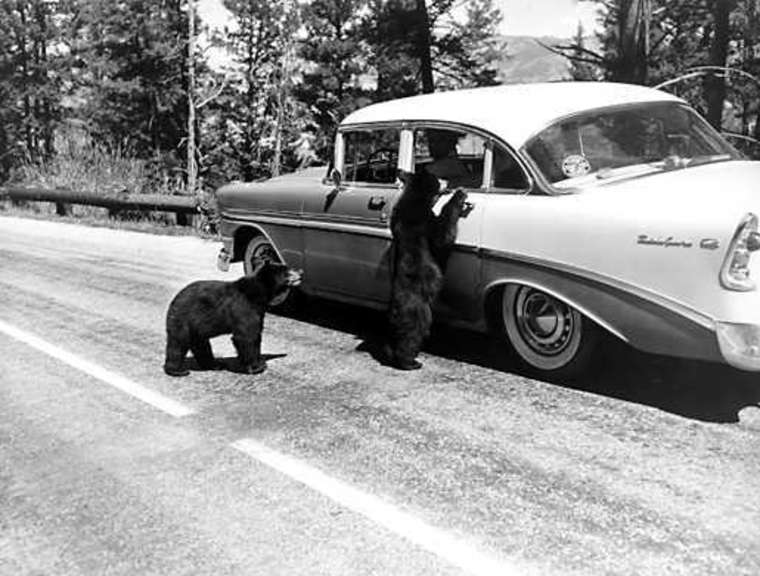

Sometimes black bears lose their fear of people. This can happen when an aggressive male becomes territorial but more often, it occurs because of repeated experiences with people and their food. Bears are quick learners and naturally curious; one handout from a clueless camper can easily establish an unhealthy habit for the bear. A few summers ago in the Apostle Islands, a bear became a nuisance after campers fed him Spam. Former park superintendent Bob Krumenaker later wrote of the incident: “A single visitor not doing the right thing with food can corrupt a bear for a season.” In the Apostles, this can lead to the temporary closure of islands to visitors. In other parts of the state, this can be a death sentence for the bear.

We pitched our tent on a site ringed by birches and then headed down the road to buy firewood from the campground hosts—and ask about the bears of course. It was a short walk, but I heard every crackle and snap in the surrounding woods. (It was a red squirrel every time.) The campground hosts told us that in fact, there was only one bear. A two-year-old, not yet fully grown. He had been loitering in the park for more than a week scavenging for food, becoming bolder each time. Most recently, he had rummaged through an unattended cooler while some campers packed up. In response, a park ranger had attempted some “behavior modification” by spraying the bear with pepper spray. The bear wasn’t fazed; he simply wiped his face with a paw and continued eating. The campground hosts pitied the bear, but they were also unnerved by his apparent fearlessness. The bear hadn’t shown aggression yet, they said, but what would happen if he did?

We thanked the hosts, took our firewood, and turned back up the road. As we wondered aloud where the bear might be, he wandered into view, ambling down the road towards us. We both froze and called back to the campground hosts. He was smaller than the bear on the sign but still larger than any dog I knew. To my surprise, I wasn’t afraid. Instead I was transfixed. The bear saw us—a group of campers in the road, mouths open, fumbling for our cameras—but he didn’t seem to care, just kept his slow, casual pace and eventually turned into the woods.

We lost track of him, but it didn’t take long before we saw him again. A couple of hours later, we drove past the dumpsters near the campground entrance. They were overflowing with the holiday weekend’s trash. The dumpsters had special latches to keep animals out, but no one had fastened them. Instead, departing campers had continued to stuff their garbage inside, even though the lid would no longer close and trash had spilled all over the ground. So much for “leave no trace.” True to form, the bear was there. Why wouldn’t he be? For an animal compelled to pack on weight for the winter, a pile of trash is a welcome buffet.

We watched him from our Jeep and got a good look at him for the first time. It was the closest I had ever been to a bear in the wild. His fur was chocolate brown with a faint blond stripe running down his back like a slash of sunlight. He stared back at us, still eating, never pausing, with something I can only describe as nonchalance. The line was blurred then, as to who was the nuisance, the bear looking for food or the gawking campers with their idling car engine. The bear slowly stood and walked to the next dumpster, and his long legs moved smoothly, almost gracefully. There was nothing bumbling or cartoonish about this animal. He was beautiful to watch, in a way I never expected from a bear. Shows what I know.

An hour later the bear was still there—despite some campers’ half-hearted yelling. The ranger had showed up and said that she would contact the local conservation officer to figure out what to do. We were back at our campsite when the officer arrived. We heard him blare his horns and sirens in an effort to spook the bear. Later, we would learn that the officer had also used pepper spray. Not long after the sirens, I was digging through our camping gear when I heard an unmistakable crack. A gunshot. Then silence. “That wasn’t a gunshot, was it?” I asked my husband. It was a dumb question. I knew it was a gunshot. It couldn’t be anything else.

The next day I visited the campground hosts to confirm what had happened. After exhausting his non-lethal methods, the conservation officer shot the bear. The host assured me that it was a clean shot and that the bear had wandered back into the woods to die. But the rangers still hadn’t found him and didn’t know if they ever would. My heart was heavy. For the rest of the trip, I couldn’t help but wonder where the bear was. I half-expected to stumble across him on a hiking trail. I hoped he hadn’t suffered long, but there was no way to know.

I’m hardly qualified to speak about issues of wildlife coexistence. I live in a suburban apartment with no land of my own. The most common animals in my neighborhood are gophers and songbirds. Their presence is entertaining, not disruptive to my life and livelihood. There’s much I don’t understand about wildlife management. That said, this incident unsettled me. It still does. It seems to me that this particular bear was killed for acting like a bear. Ranging through the woods, he stumbled onto what was essentially a bear grocery store and didn’t want to leave. Then again, I was there. The story is more complicated than that. The truth is, the bear had been habituated to people before he discovered the overflowing dumpsters. His natural wariness had already faded. But the question we all asked at the time—me, the park rangers, the campground hosts, the conservation officer—was why? How had such a young, inexperienced bear become so fearless? Maybe a camper fed him Spam. Maybe the bear had previously discovered too many unlatched trash cans. Or just one trash can, setting into motion a pattern of behavior.

Not long before our camping trip, the internet was outraged at the death of Cecil the lion. After the bear’s death, I thought about Cecil and about how it doesn’t take a poacher to end the life of an innocent animal. Negligence is enough. In many ways, it’s hypocritical to campaign against poaching in Africa and then engage in careless behaviors that harm wildlife in our own communities. The conservation officer didn’t kill the bear. More likely, handouts and littering killed the bear. Irresponsible people. Campers like me.

That same weekend, a bear cub wandered into a campsite at Tettegouche State Park, 20 miles up the road. It was the time of year when cubs leave their mothers and begin to navigate the world on their own. When the cub saw people at the campsite, he was downright scared. He quickly hid behind a tree stump, not knowing what to do next. The campers left him alone. Eventually, the bear moved on and wasn’t seen again.